I have successfully completed my final work assignment with the Solar Energy Foundation in Ethiopia and on Monday I returned to the US. However, after finishing my SEF gig and before returning home, Robin and I traveled for 10 days around Ethiopia. We spent most of that time in South Omo, the most underdeveloped part of one of the poorest states in the 11th poorest country on Earth. And it was like walking through the pages of National Geographic. There are 22 different tribes living in this region, speaking about as many different languages. Here are the highlights:

The Dorze tribe reside on a string of mountaintops in the south of the country. They live in 20 foot tall beehive shaped homes. The height allows for a poor man’s cathedral ceiling: bamboo covered by banana leaf thatch. Inside the home a small smoky fire continuously burns to keep the insects down and to ward off the (relatively) cool temperatures at their 8000 foot high elevation.

We went into one of the homes. It housed a family of six, plus three cows and three sheep, humans separated from the livestock by a woven banana leaf screen. The cow area is very important: If the husband comes home drunk and tries to beat his wife, she will retreat to the cow side of the house…a recognized safe zone. If he should violate that safe zone, she will report him to the village elders. They will penalize him by requiring the purchase of a cow (at the princely sum of $300) which he must butcher, roast and share with the village. Perhaps this seemingly simplistic tradition keeps domestic violence to a very low level.

The Mursi tribe provided us a big culture shock. Their claim to fame is a custom believed by them to increase female beauty, but certainly believed by most everyone else in the world to be barbaric. At about age 20 a young woman becomes eligible to marry…and begins to wear a clay lip plate. A slit is cut inside her lower lip and over the course of the ensuing year, larger and larger clay disks are inserted into the slit until her distended lip can accommodate a 6 inch diameter disk. The larger, the more beautiful.

I have never seen a sight as interesting…and as disturbing as a village of 600 people with virtually every woman over age 20 either wearing a lip plate or displaying a sagging lower lip, dangling down to her chin – – when the plate was not being worn. Many Mursi women were topless and I am substantially more in favor of that custom than a stretched, deformed lower lip. I saw only one women of lip-plate age without a stretched and distended lip. She had gotten pregnant before marriage, and as a punishment by the tribe, she was forbidden to ever slit, stretch, and wear a lip plate. Bummer.

But then again, who am I to judge another’s culture? I am thrilled to have seen such a spectacle, even if I strongly object to it.

And speaking of objectionable spectacles, we spent an entire afternoon at a Hamer bull jumping ceremony. Nothing wrong with bull jumping, just with the custom that proceeds the jumping. A twenty-something single man proves he is ready for adulthood and marriage by running across the backs of eight bulls standing flank to flank. Only one man attempts that feat at each ceremony, but hundreds of Hamer participate in ceremony.

The first – – and the truly objectionable – – part of the ceremony is the whipping of the women. Female supporters of the jumper-to-be line up to be whipped (always by a man) with a long stout switch. And we are not talking about playful taps across the shoulders. Each woman asks to be whacked really hard. I could hear the snap across her back. I could see the welts rise. I could see the blood lines form on the welts. Most women from late teenage and older bore permanent whipping scars across the back.

A most surprising aspect of this ritual beating is that the participating women, dozens of them, seem to do this willingly. They taunt the whipper to hit them harder, they get back in line for a second and third beating. The more and the harder they receive, the more support they show for the jumper.

After the whipping, and a bit of dancing by the women, and some face painting by the men, the entire group of well over 200 Hamer (and a few tourists) walked 15 minutes into the bush to the bull jumping site. The jumper is presented to the crowd – – naked. Then he takes a running leap onto the back of the first bull, scampers across the backs of the remaining seven bovine, and jumps to the ground…where he catches his breath, then repeats the journey from ground to bull back to ground – – two, three, four, five, six times. Each time successful, no falls.

This triumph was especially satisfying for the jumper’s sister. Had he failed, she would have been beaten, just like the willing female supporters before her, but this time by the entire crowd. Had the jumper botched his quest, punishment would be have been meted out to his sister under the belief that she did not feed him sufficiently to succeed. Consequently, brother’s success was especially sweet for sister.

Most of the Hamer came to the bull jumping dressed to celebrate. Men were bare chested with ornamental beads around the neck, biceps and waist. Women work goat skin skirts and loose goat skin tops to cover their breasts, but nothing on their backs…all the better to receive the lashes from the stout switch. And those who really wanted to stand out had a mixture of fresh red clay and butter applied to their page-boy-length, tightly curled hair. The mixture, also rubbed on the shoulders and sometimes the face, glistened in the afternoon sun.

So eye catching, so memorable. Now if they could just eliminate the bloody beatings, I would be a total supporter of traditional Hamer culture. But at least they didn’t wear lip plates.

In every tribal region we passed through, young children (mostly boys) would – – upon seeing our vehicle approach – – dance by the side of the road. Dance style would vary depending on the local tribe: shaking hips or bootie, waggling one raised leg, bouncing up and down from deep knee bends, making vertical leaps into the air. Even waking on stilts (with white chalky clay on the face and torso.) Initially I thought the purpose was a sort of greeting, but more likely it was a creative request to pose for a (paid) photo. However, had we stopped to photograph and pay each dancer, we would have had no time to complete our journey. There were that many dancers.

The corruption of policemen in Africa is legendary. Being shaken down for a bribe or charged with a made-up traffic violation is rife on the continent. But not so in Ethiopia. In my entire three months here, not a single time. That is until my final week. Our driver, Osman, was flagged over by a policeman who requested that we make room for the cop’s friend in our privately contracted vehicle. Osman protested, said we were foreign tourists who had paid for the vehicle. The policeman calmly explained, “No problem, but we will have to pull your van off to the side of the road and inspect every bag.” Osman decided that discretion was the better part of valor, so we made room for the policeman’s friend in our vehicle. We didn’t talk to him much though, we were not especially gregariously inclined at this point.

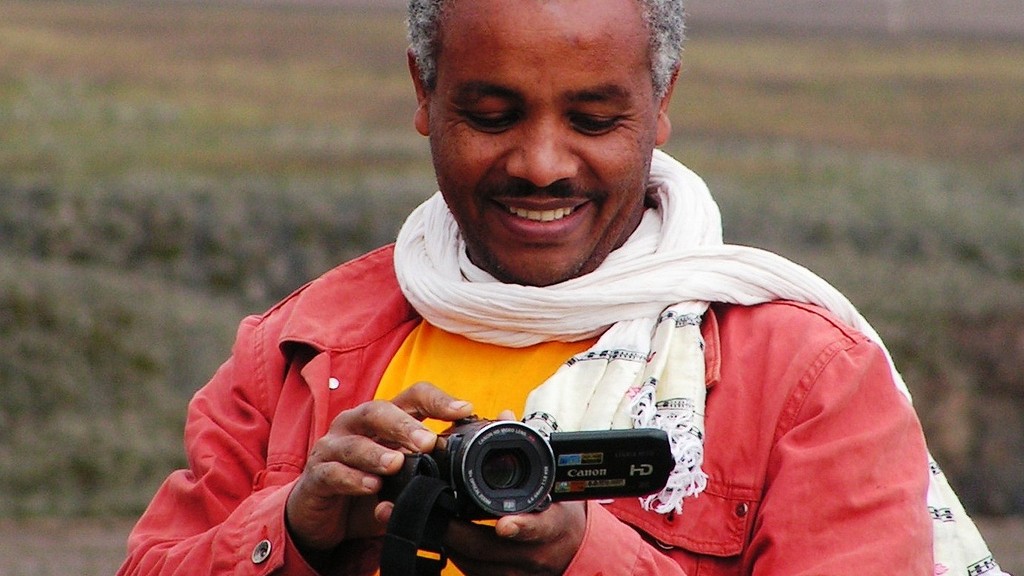

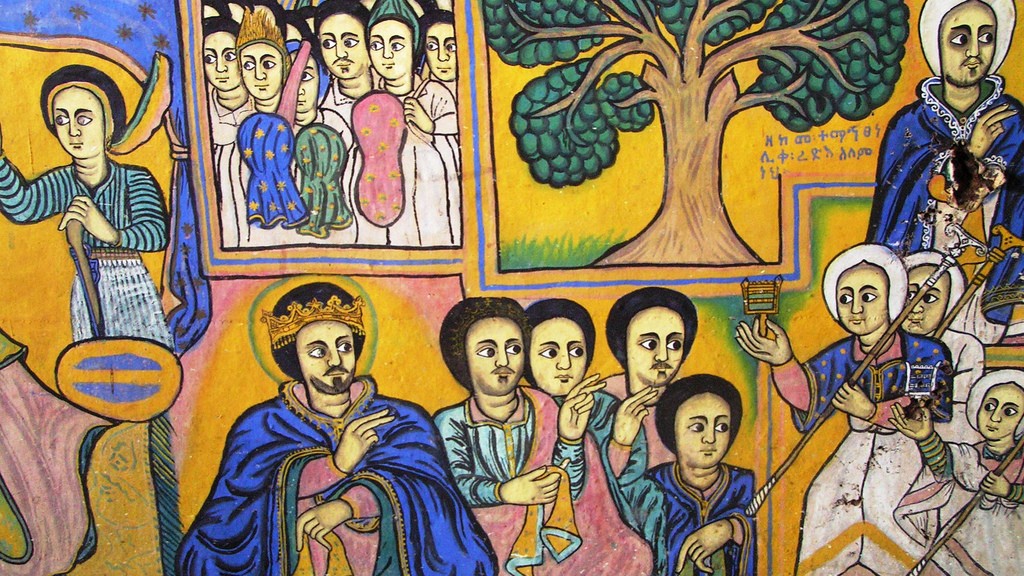

Our final stop, a one hour flight north of Addis, was the small town of Lalibela, Ethiopia’s most famous historical treasure and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. About 800 years ago King Lalibela, during a 23 year burst of religious devotion, commissioned the carving of ten churches (one for each of the Ten Commandments) out of solid bedrock. Legend has it that St George complained to the king that not one church was named for him, so Lalibela added an 11th – – called Gyorgis Church. Many of the churches are connected by underground tunnels also cut through the rock. Quite a fun way to travel from church to church.

They say that these rock hewn churches at Lalibela would be considered one of the seven wonders of the world if they were not located in the remote highlands of a relatively obscure country in Africa. It is not totally clear to me who “they” are, but the supposition is correct. A three story tall church, ornately carved out of solid rock is beyond description. You’ll just have to come see them yourself…or check out my photos.

In the late afternoon, after we finished our full day visitation of these 11 spectacular churches, we walked down a crooked rocky path through a cluster of homes. A young, but very self possessed, preteen girl stepped from the gate of her family compound and inquired, “You want buy scarves?” Interested in such a purchase, we entered her walled compound: a dirt courtyard surrounded by four mud and stone buildings. We sat on a stone ledge in the compound while the girl, her mother, older sister and a friend displayed dozens of hand loomed cotton scarves. After several minutes of very friendly bargaining with the appointed negotiator, the 12 year old girl, we made our purchase.

The family was so taken by the size of our purchase – – 8 scarves – – that they invited us to stay for coffee. An older sister roasted the beans over charcoal, then brewed a rather strong cup for each of us. To go with our coffee the mother brought us freshly cooked injeera and a mound of spicy red chili. During coffee hour, the 12 year old quizzed Robin and me on Amharic vocabulary. We answered only 2 of 20 correctly. She was asking difficult words. Like hello and yes and chair. Who knows that?

When it came time to leave, the bright young girl walked us down the path in deepening evening shadows to the main cobblestone pedestrian thoroughfare. She stopped, pointed at her shoes, Croc knockoffs with a large split in the back. “For me you have extra shoes in your hotel room?” We didn’t. None that would fit anyway. My well worn Nikes were years too large for her. Instead we offered her 20 birr (about $2 – – the amount a new pair of shoes would cost in Lalibela.) Too proud for that, she rejected our repeated offers of the cash…even when we suggested she give it to her family.

We ultimately went separate ways, us with the money back in our pockets, but much richer from the cultural interaction. And she, equally culturally richer, but still wearing her broken down Crocs.

And two days later we returned to the US, so thus ends this series of Ethiopian updates. I wish you all the best.