I have seen the future. At least the future of travel. Two weeks ago, on my way to Mozambique on assignment, I connected with Delta through Atlanta. Boarding my overseas flight required no need to show an ID nor a passport, no need to show a boarding pass. I just stood in front of the visual scanner and in a couple of seconds the screen read, “Welcome, Mr. Nichols to Delta flight 200 to Johannesburg.” Facial recognition is here. I expect this secure and rapid passenger identification process will eventually be the way to board all flights. Discussion about invasion of privacy we can save for another time. I was blown away by the technology.

My assignment is anything but high tech. My NGO for the southern tier of Africa, CNFA, asked me to help them formulate their development program for the upcoming five years in Mozambique. I have concentrated on businesses serving small holder farmers. Such businesses include seed suppliers, tractor services, irrigation providers, agricultural loan companies. My job has been to interview a range of these service suppliers in three of Mozambique’s eleven provinces to determine what sort of development assistance they and their client farmers will benefit from. We expect to offer 44 volunteer assignments in the service sector over the next five years. Those of you interested in, say, tomato irrigation better get your bids in early.

We drove west from Nampula toward the tomatoes. We passed burnt corn fields. Now is the dry season, the farmers have harvested their grain and they remove the now bare stalks and crop residue by burning…effective, but bad for the soil. Fire kills micro organisms that are beneficial to soil fertility. But without mechanization (a tractor, say) or even oxen, clearing the crop residue or plowing it back into the soil is not likely. Fire is likely. And it burns not just field rubble, but also nearby trees. Some agricultural NGOs are trying to convince the farmers to replant trees around the perimeter of their fields. Trees provide a habitat for honeybees. And wild honey is an especially valuable commodity as it brings in needed cash to poor farmers. But meanwhile I mostly see charred fields.

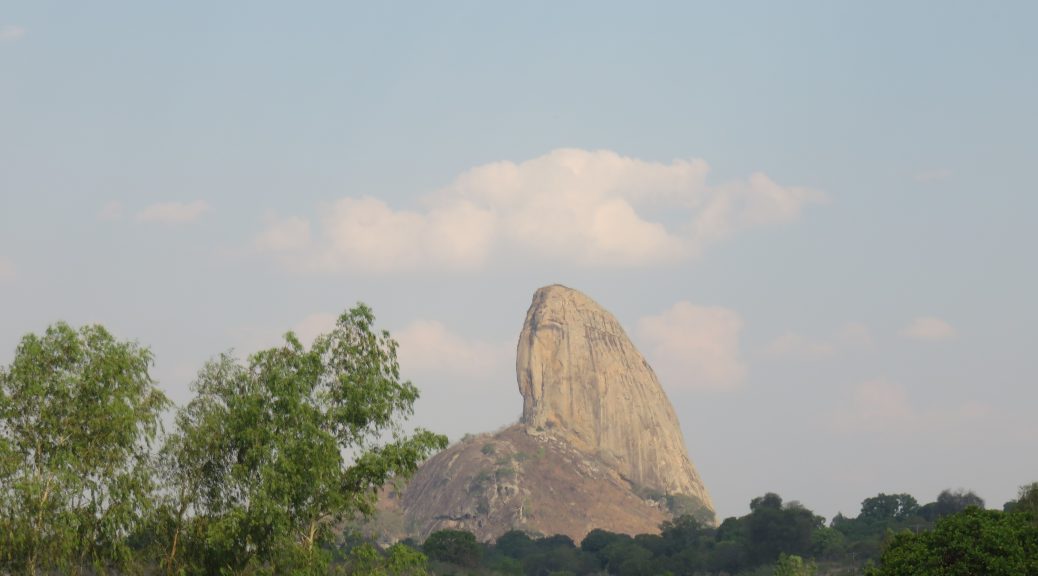

I never tire of the rural scenes along the highway: kids in uniform on their way to school, mud brick homes with thatched grass roofs, wandering goats and chickens, and at this time of year, fruit and nut trees heavily laden with their produce. Mango and cashew trees were especially endowed. On this stretch of road I saw something new, striking rock formations called inselbergs. These are giant granite mounts jutting hundreds of feet out of the surrounding plain. (see photo above)

Beyond the tomatoes we came to the onion fields of Malema. In this country Malema onions are famous for their flavor. Some call these onions, the Vidalias of Mozambique. Actually, no one calls them that. No one here has ever heard of Vidalia, Georgia. I only called them that because it sounded clever.

Some 500 miles south of the onions lies Chimoio, the capital of Manica Province. In the countryside surrounding this small provincial city are many maize and soy bean farmers. Both crops are used to produce poultry feed needed by Chimoio’s chicken growers. We met with one organization that is assisting small farmers to improve their growing techniques and to band together in order to receive better prices for their crops. This assistance comes in form of Village Based Agents. VBAs are local farmers with leadership talent. They are trained in advanced agriculture skills and in marketing. By improving their fellow farmers’ yields and by finding markets for the crops, they can improve the lot of these small holder farmers. In reward for successful sales results, the VBAs receive a commission. The most successful among them will bring in an extra $800 per year. Add that to earnings from farming and from honey, one should be able to replace his grass roof with a corrugated aluminum roof in short order.

One morning while in Chimoio, I went out for my (slow) morning jog. I passed the Che Guevara Bar, complete with his famous image. Then a second with the same name and image, and soon, a third. A couple of observations: First: this guerrilla leader from the 60s was a folk hero in Mozambique. Back in the 60s, 70s, and 80s Mozambique was supported by the Soviet Union and Cuba, so Che Guevara became well known and loved. And apparently, he is still revered enough for three different and independent bars to claim his name. Second observation: trademark protection in Mozambique is not well developed. I also came across multiple Bamboo Bars. This morning’s jog took me down a gently sloping road. However, on the return of my out-and-back route, someone had ratcheted up the incline. The return was much steeper. I’ll have to research the physics behind this phenomenon.

The changing climate is frequently a topic of discussion among farmers. Despite what some political leaders say, the farmers know that rainfall and temperature are changing. We met with an American NGO that assists these farmers. The NGO had started a program called Climate Smart Agriculture. The director of this organization told us that the current US administration – – which seems to deny that humans play any significant role in climate change – – did not like that name containing the word, Climate. Consequently, this NGO changed the program name to Resilient Agriculture. They continue to do good work under the camouflaged name.